Taking Medicine to the Ends of the Earth

Poverty and distance are the enemies of health.

In the rich world, high quality medical care is usually a short drive away, because there is an average of 3 physicians for every 1,000 people. In South Africa, there is 0.8 per 1,000, though it is one of Africa’s most prosperous countries. In Tanzania, one of the region’s poorest countries that is not racked by war, it is only 0.3 per 1,000.

In the world’s developing nations, some 3.1 billion people live in rural areas and more than half of them live on US$2 per day or less. That makes it hard for them to get to a caregiver, and does not buy a lot of medical care when they do. Nor are rich-world citizens immune to the curse of distance. Whether in rural counties or remote mines and wellheads, people can find themselves far from help when help is needed most. That is why health systems around the world turn to satellite to extend the reach of medicine and defeat threats to public health before they become catastrophes.

Have Mercy

Satellite does more than help cure patients. It also helps create local healers. Mercy Ships delivers classes via satellite to local medical staff to build up a lasting skills base. They also use satellite keep the corporate ship afloat. Videoconferencing via satellite replaces many in-person meetings, saving on travel. Shipboard volunteers also contribute their stories through satellite video to help with fundraising back in the US.

Mercy Ships is hardly the only nonprofit using ships to deliver medical care. A Bangladeshi charity, FRIENDSHIP, operates its own fleet of hospital ships. They use SATMED, an e-health platform developed by satellite operator SES, working with European NGOS, which is funded by the Luxembourg government. In addition to communications, SATMED provides software tools from electronic medical records and tele-radiology to e-learning. SATMED is also also at work in Benin, where it links three hospitals to improve mother and child health after childbirth, and Niger, where it enables local practitioners to consult with national and international doctors.

Telemedicine at the Extremes

“Telemedicine” is the name for this remote delivery of care, consultation and training – and it has a huge and growing impact on people’s lives. According to a study of a single telemedicine network by the American Telemedicine Association, medical consultations between rural hospitals and metropolitan medical centers saved more than 850 lives over a four-year period. Review of all medical orders by hospital-trained pharmacists at the medical center prevented more than 11,450 serious drug interactions and allergic reactions. Improved oversight of acute care for the most seriously ill saved 28,500 days in the intensive care unit and reduced costs by $44 million.

Ships at sea, oil platforms and remote mining sites face isolation almost as extreme. To meet their needs, George Washington University (GWU) teamed with software developer Diginonymous to develop Digi+Doc. It gives its users voice and video access to more than 500 physicians and specialists at the GWU Medical Facility. VSee, a private company, provides telemedicine support for two Shell oil platforms off the Nigerian coast, which allows the single medic on duty to bring aboard the expertise of multiple physicians. (The VSee system is also in use aboard the International Space Station for everything from medical consults to school presentations.) The grandfather of satellite telemedicine is surely the International Radiomedical Centre in Rome. Using the simple tools of telephone and email via satellite, it has cared for more than 50,000 maritime patients since its founding in 1935.

Fighting Disease Outbreaks

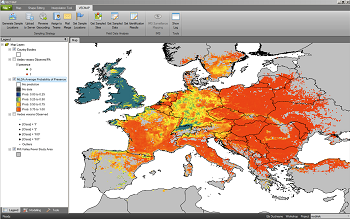

A different satellite technology holds out hope for stopping epidemics before they begin. Insects are responsible for spreading many diseases, and climate change, trade and travel are constantly driving insect populations to new areas. A consortium of Belgian companies, supported by the European Space Agency, has developed a software and services package called Vecmap. It improves how field researchers gather data and how public health authorities use it. The work begins with field researchers placing insect traps and checking them periodically to identify, count and test the insect found there. They enter data into the smartphone app, which captures exact GPS coordinates as well, and Vecmap pools the information to map high-risk areas on a satellite images. This is invaluable information for public health officials working to prevent the next epidemic. It also helps field researchers find those traps in the field as well as select new target areas, which are the most time-consuming and expensive part of data-gathering.

Health is the greatest gift. Wherever poverty or distance denies that gift to the world’s people, satellite brings a healing hand and hope for a better life.